|

|

As the country numbers get higher, people just keep getting awesomer. (That was grammatically correct, right? No? Whatever.)

Our Rwandan chef-for-a-night, Placide Magambo, is a fellow that I’d never met in my life before he fed me. Sure, we had a friend in common – a fantastic guy named Aaron, who you really should follow on Twitter. And Aaron had arranged to have Placide prepare a home-cooked meal for us, based on his mother’s recipes.

But still: the guy had never actually met me. And he made dinner for 20 of our friends, even though we were complete strangers. Amazing.

Placide is one of those guys who immediately feels like a brother. He’s an accomplished journalist who knows a thing or two about media oppression, and he had seen his share of unpleasantness before coming to the United States. He’s a vibrant, insightful guy who builds deep, warm friendships – just seeing him hang out with a few of his American “sisters” was a beautiful thing to watch.

And on a higher-calorie note: the man can cook.

Placide treated us to an amazing tour of Rwanda’s best dishes, with some long-distance assistance from his mother (thank you, Mom!). Placide prepared a magnificent Rwandan rendition of pork stewed in tomatoes, onions, and green beans:

apparently, Rwandans do tasty things to pigs

Placide also prepared a nice, fresh salad, featuring lettuce, tomato, boiled egg, onions, and sliced avocado (avocado!!!), tossed in a nice vinaigrette:

a nice, healthy salad…

But that’s too healthy. Let’s get to the exciting part: carbs.

You know that I love ugali — wondrously dense balls of white cornmeal, known as sadza or nsima or nshima in southern Africa — but Placide’s Rwandan version was just a little bit different, made from a delicious but not-super-photogenic blend of white cornmeal and cassava:

but by ugali standards, this is basically a supermodel

And then there were more carbs. Here are some phenomenal fried potatoes, which are always a work of art when they’re fresh:

And then there was pelau, the Rwandan version of rice pilaf, featuring bits of… whoa, there’s some serious ginger in there. You can’t really see it, even when Placide is pointing right at it. But holy frijoles, this stuff had a delicious, ferocious, ginger-y kick to it:

And the real star of the show was the isombe, arguably Rwanda’s national dish, featuring stockfish, peanut sauce, and potato leaves — which, if I remember correctly, Placide’s mother sent straight from Rwanda:

even better than a supermodel

If you’ve never tried the stuff, isombe is another variation of those intensely flavorful stewed-greens dishes that you can find throughout Africa — it brought back fond memories of Cameroonian ndole and Namibian omboga and Central African yabanda, just to name a few of my favorites.

And as usual, the meal was another wonderful excuse to bring 20 amazing people together for an evening of feasting — including at least one amazing musician who had his serious, isombe-eating face on:

Rwandan combo platter, gone amazingly right

Huge thanks to Chef Placide Magambo for the amazing meal, the legendary Aaron Leaf for making this happen, and the even more legendary duo behind Todd Reynolds Music for hosting us all. Isombe!!!

|

|

|

Let’s get right to it:

Yep, that’s a picture of two priests and a school principal. And yes, the gentlemen are drinking home-brewed millet beer from a communal clay pot, using long, homemade straws. But you probably figured that out already.

Here’s how all of this happened: I somehow met a Ugandan guy named Brian (from We Dream Africa), and he introduced me via email to a Ugandan named James, who happened to be the organizer of a Ugandan independence day celebration. He graciously invited me to tag along for the celebration, held in the gymnasium of the Saints Philip and James School in the Bronx.

Sadly, Brian couldn’t make it that night, and neither could the cameraman who had planned to accompany me. So I walked into the school gymnasium alone, without knowing anybody at the event. And here’s when you know that you’re in the presence of a wonderfully welcoming culture: from the moment I walked in, friendly Ugandans kept approaching me to strike up conversations, answer my questions, and make sure that I felt comfortable.

It was incredible – I can’t even begin to tell you how much I learned about the country that night, and I lost track of the number of fascinating, friendly people I met, including a visiting priest named Father Charles who was enjoying his first-ever trip to the United States, several entrepreneurs and teachers, a social work professor, a few graduate students, and some United Nations staff members.

But you’re probably not here to hear about the amazing Ugandans I met. This is a food blog, so you’re probably here for food:

amazing food, surrounded by amazing Ugandans

So yes, that’s an epic buffet, prepared by a fleet of friendly Ugandan women. The meal highlighted the wondrous diversity of Ugandan cuisine, which is intensely regional. Some African cuisines center around a single, starchy staple, like Malawian nsima. But depending on where you are in Uganda, you’ll see completely different staple starches, including rice, cassava, yams, matooke (mashed green plantains, often cooked in a banana leaf), taro, posho (a corn-based relative of ugali), millet, and chapati, among others.

a small sampling of Uganda’s carbo-licious splendor

The plethora of starches (yup, I was just looking for an excuse to use the word “plethora”… you’re welcome) was accompanied by a herd of excellent protein dishes, including a fantastic roasted chicken, some stewed pork, and two different versions of peanut sauce. Interestingly, one of them had been slow-cooked inside a banana leaf – I was told that this particular version was reserved for special occasions, since it takes literally a full day to prepare:

epic Ugandan combo platter; yes, you can taste the difference between the slow-cooked peanut sauce and the not-as-slowly-cooked peanut sauce

This meal, of course, was prepared to celebrate a special occasion: Ugandan Independence Day. And in keeping with Ugandan cultural traditions, all special occasions are followed by music and dancing. “It’s part of our culture,” one of my new Ugandan friends explained, “You have to dance at these events!”

But right before the dancing began, the school’s principal, a deeply charming Irish-American named Cathy, came over to introduce herself. (Apparently, I looked a little bit out of place in a sea of Ugandans, even if the sea of Ugandans had ensured that I felt perfectly at home.) When I explained my food quest to her, she exclaimed, “Oh, you need to come with me!”

Then she gently grabbed me by the arm and pulled me across the school courtyard, into the adjacent church, and upstairs into the priest’s apartment. That’s where millet beer happens.

millet beer… happening in a not-terribly-traditional glass pitcher for now

Cathy’s nephew, Michael, turns out to be one of America’s foremost experts on Ugandan millet beer, and he told me exactly how the stuff is made. The only trouble is, I’m a little bit worried that my memory of the millet beer recipe has already been clouded by… well, lots of millet beer.

But here’s what I understood about it: basically, you take a pile of millet, and leave half of it outside for a week or two to collect natural yeasts to start the fermentation process. The other half of the millet is then pan-toasted. Then, all of the millet is ground into a powder and fermented in water. After a few days – presto! – millet beer. The “raw” millet beer is then mixed with hot water immediately before it’s consumed.

I absolutely loved the stuff. It reminded me a little bit of an unfiltered, unsweetened sake – it didn’t have even the slightest hint of sugar, but had a nice, toasted flavor, and plenty of sediment to give the beer some texture. Actually, it has so much sediment that you have to drink it through a long straw with a metal screen on one end.

tool of the millet beer-drinking trade

And since we were in Father Steven’s apartment, the next thing I knew, I was drinking with a couple of priests, passing the long straws back and forth so we could guzzle our respective shares of the beer. We chatted about Uganda, and Tanzania, the priests’ lives in America, and the various parishes they’d led over the years. Principal Cathy started talking about some of the antisocial behavior by her students at the school, and she and the priests started brainstorming ways to improve the moral strength of the children in their schools and their parish.

I wobbled in my chair a little, admiring my companions: even on a Saturday night, they were plotting ways to make their community a better place.

and I was plotting a very mild hangover — with a proper Ugandan clay pot this time

And at some point, I excused myself – after all, it was late on a Saturday night, and I had a funny feeling that the priests had some work to do the next morning.

Endless thanks to all of the amazing Ugandans (and honorary Ugandans — you know who you are!) who made this an incredibly memorable evening: James, Brian, Proscovia, Father Steven, Father Charles, Cathy, and Michael, among countless others. You all know how to make an American boy fall in love with your country — even if he’s never set foot there.

|

|

|

I can’t claim to know much about Turkmenistan, but here’s one thing that makes me love the country immediately: Turkmenistan officially celebrates National Melon Day on the second Sunday of August. It’s actually a major national holiday, sanctioned by the government.

You might think that this is some sort of political slogan, but in Turkmenistan, it’s actually somewhat true: there’s a melon on every table. At every meal. Including this one:

Yeah, I think I’m about to love Ashgabat, too

I’m a little bit obsessed with melons, apparently — even when I’m asleep. After gaining 20 pounds (I’ve eaten food from more than 150 countries, cut me some slack!), I briefly went on a low-carb diet – and dreamed of melons several nights in a row. I am not making this up. (And no, it’s not a metaphor, either.)

But as much as I love melons, I get even more excited about a fantastic conversation with a warm Turkmen family – especially if it involves a home-cooked meal.

Can you spot the non-Turkmen in this picture? (photo by Andrew Guidone)

When I arrived at the home of the Notomelette family on a beautiful Saturday afternoon – accompanied by a wonderful filmmaker from NYC Media – our hosts were ready for us: the dining room table was already covered with homemade dough, the precursors to some homemade beef and pumpkin manti:

manti in the making

Our gracious Turkmen hosts — Tylla, Serdar, and their son, Dovlet — then demonstrated the entire process of making the manti. A video version is hopefully on its way to a television near you, but here’s the pictorial version:

photo by Andrew Guidone

And yes, the manti were every bit as amazing as they look. You really can’t beat fresh, hand-sized beef-and-pumpkin dumplings, straight out of the steamer — especially when they’re topped with a little bit of melted sour cream, and served with a pair of traditional Turkmen salads. Our meal featured a classic shepherd’s salad, and a garlicky beet salad with sour cream:

photo by Andrew Guidone

And the Notomelettes were just getting warmed up. They also prepared plov, another thoroughly lovable Turkmen staple, featuring blissfully chewy steamed rice, cooked with beef, carrots, onions, and a whole bulb of garlic to give the dish some extra flavor:

photo by Andrew Guidone

The Notomelettes also explained that no Turkmen meal is complete without a nice loaf of chorek — a round bread made in a clay oven, called a tamder. You might notice the resemblance to a few other Central Asian breads: lepeshka, widely featured in Bukharian Jewish restaurants in NYC, or Armenian choreg – which is shaped similarly, but tastes more like a lightly sweetened coffee cake.

Anyway, this chorek came straight from the motherland itself, brought back from Tylla’s recent trip home to Turkmenistan. The Notomelettes insisted that the chorek is better when it’s fresh, but it was still awfully tasty, with a distinctively crispy exterior and a nice, soft interior.

And of course, a plate of fresh melon was lurking during the entire meal, patiently waiting its turn behind the plov:

photo by Andrew Guidone

By the time we munched our way through the melon and snapped a few more photos, we’d been in the Notomelettes’ home for about five hours — which gave us time to learn TONS about Turkmenistan and the nation’s culinary culture. A quick sampling of my favorite tidbits:

- According to legend, Turkmens kept their boots shiny by eating roasted lamb with their hands – and then wiping their fat-smeared fingers on their leather boots to give them a nice, supple sheen.

- Testosterone poisoning is a real thing. Manti and plov are often made with lamb in Turkmenistan, but when the Notomelettes arrived in the U.S., they felt that the lamb tasted worse than back home – but inconsistently so, maybe half of the time. Apparently, the bad-tasting meat comes from un-castrated male lambs. So this is no surprise to any woman who’s ever dated me, but testosterone can apparently be a very, very bad thing.

- In their years in the U.S., the Notomelettes have tried literally dozens of varieties of rice, but none of them have the same chewy, sticky consistency of the rice back home in Turkmenistan. Interestingly, the same is true of carrots: the American varieties taste more or less the same as the ones back home, but the Notomelettes noticed that cooked American carrots fall apart much faster than their Turkmen counterparts — and they’ve tried dozens of varieties in their plov since arriving in NYC.

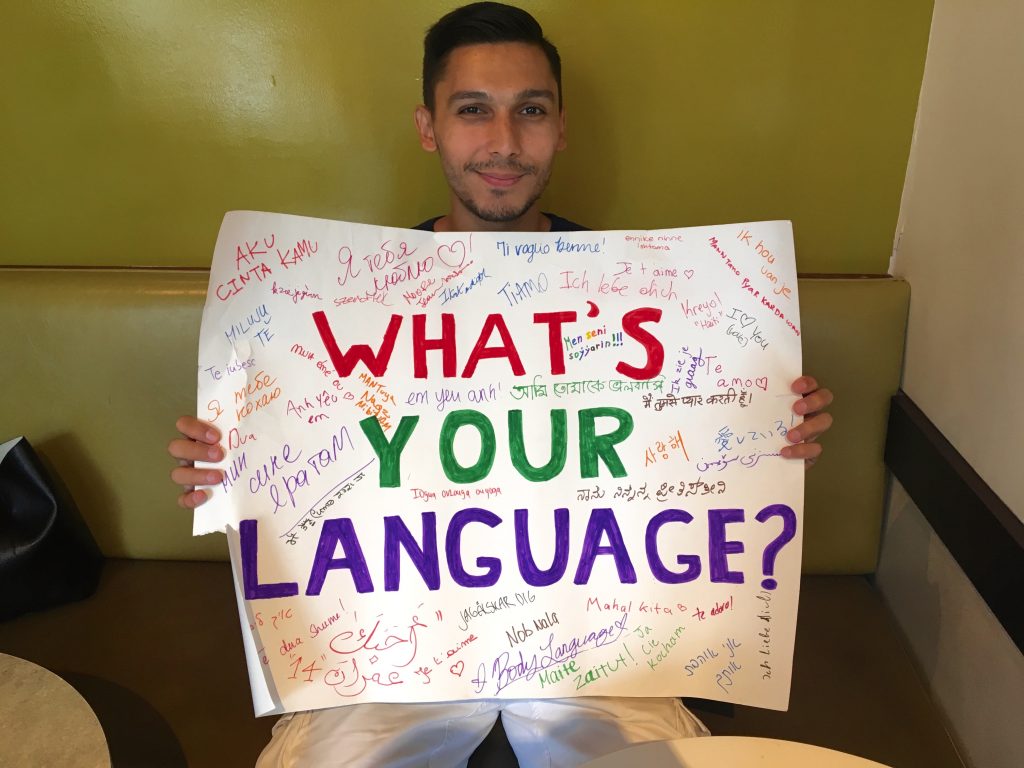

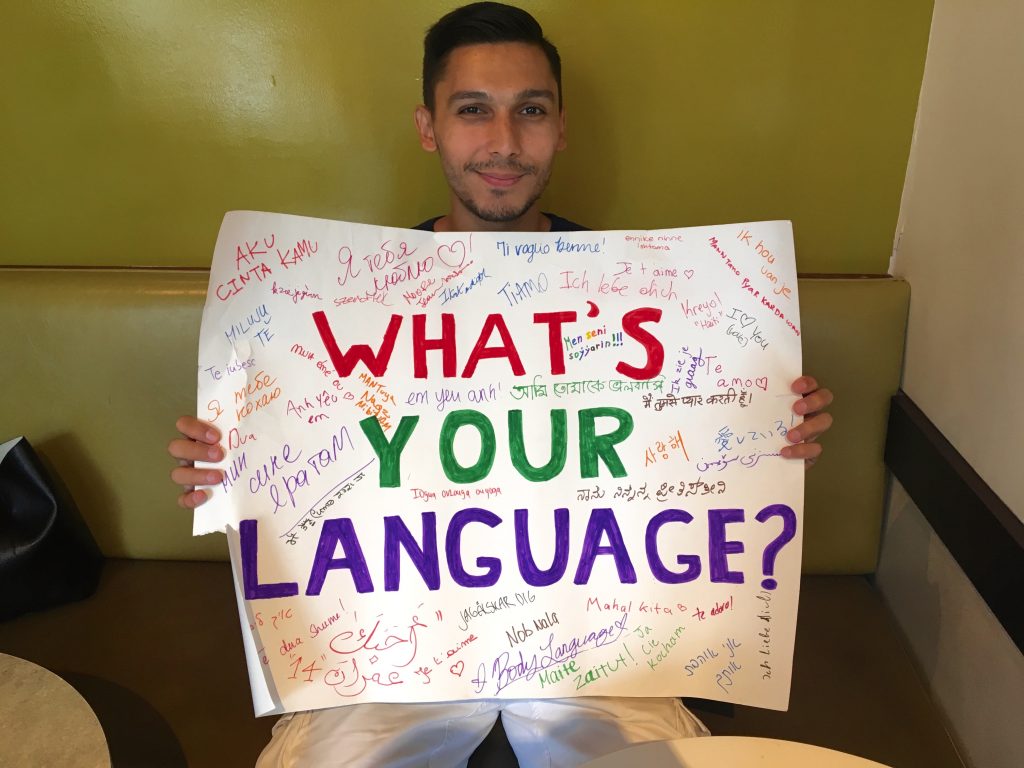

And in case you’re wondering how, exactly, I weaseled my way into a meal at the Notomelettes’ home, here’s the story: through the internet grapevine, I heard about a Baruch graduate student named Dovlet who had produced video of people saying “Happy New Year from New York!” in 100 different languages. His follow-ups have included videos of 100 people saying “I love you” and explaining what they’re thankful for in 100 different languages. And, well, New York dudes with quixotic international quests need to stick together.

So if you see this guy, talk to him in whatever language you speak – and good things will probably happen.

Well, my language is food — thank you for asking!

Huge thanks to Dovlet Notomelette and his parents, Tylla and Serdar, for graciously inviting us into their home and allowing us to film them until they wanted to toss us out the window. Huge thanks also to the always-wonderful Andrew Guidone for providing much better camera work than I could ever dream of.

|

|

|

Let’s get this out of the way first: yes, I ate four plates of caterpillars. Yes, I very much enjoyed them. And caterpillars contain four times as much protein per ounce as unadorned chicken breasts, so I could even make horrible puns about eating healthy grub(s).

Hey, stop squirming! I mean you — not the caterpillars.

Now you might be wondering: how, exactly, does an American end up eating home-cooked caterpillars, imported from the Central African Republic?

Well… I was at a Super Bowl party a year ago, watching my beloved Denver Broncos kick some butt, and I started talking about food. (Surprise!) Suddenly, some American guy I had never met stood up, and said that he knows some guy, and that guy knows a guy from Central African Republic (CAR).

A few months later, I finally managed to meet that guy from CAR – a fascinating fellow named Erick.

Erick has done all sorts of incredible things in his life. He works as a Sangho-French-English translator, runs a small import-export business, and did some incredible charitable work back in CAR. He has lived and traveled all over his home country, and knows more about CAR’s regional languages, cultures, and culinary traditions than anybody you could possibly meet.

Erick graciously arranged a one-night culinary tour of CAR, prepared by a wonderful woman named Aline. Aline is Erick’s cousin, but they met only after Erick arrived in the U.S. six years ago. Nevertheless, Aline agreed to prepare food for 20 non-Central African strangers in Queens, including my favorite TV producer, the creator of an African educational platform called WeDream Africa, a classical violinist gone wrong, and an outstanding Croatian vocalist.

This struck me as an unbelievably generous thing for Aline to do. She’d never met any of us, and she took an entire day off from her job as a home health aide in New Jersey, just to cook for us in Queens. Amazing.

Aline’s cooking, of course, was just as amazing. Even if the picture of this one might make you squirm: yabanda, made from caterpillars, stewed in finely diced vine leaves (called koko in Sangho, gnetum in French), onions, and a scotch bonnet pepper…

If you’re thinking “ewwwwwww!”… well, you might be wrong. If I blindfolded you, fed you a spoonful of yabanda, and told you that you were eating some sort of delicious fried mushroom cooked in tasty greens, you’d probably believe me. The texture reminds me a bit of fried tofu – reasonably firm, and somewhat chewy – but with a slightly nutty flavor.

Incidentally, the CAR government conducted a marketing campaign to encourage residents to grind up the caterpillars and add them to baby food, since they’re such a great source of protein and other nutrients. Seriously: as far as I can tell, these little buggers are better for you than anything you can buy at Whole Foods.

Plus, what’s more fun than watching an American dude eat a bug?

Aline also brought a second type of caterpillar from CAR, but this batch had been smoked and stewed in onions, giving it a richer flavor. Again, if I told you that you were eating some sort of smoked mushroom – or a mushroom cooked with a tiny bit of smoked fish – you probably would have believed me. Well, with your eyes closed, anyway.

And just so you stop squirming: Aline’s cooking prowess went far beyond caterpillars. She also prepared a wonderful dish called kpokpongo, featuring gboudou leaves — which grow only in Central Africa — stewed with stockfish, onion, vegetable oil, and yellow peppers:

And since Central African Republic is located in the heart of Africa, our culinary tour also featured a full variety of starchy staples that you might see elsewhere on the continent, including rice, white cornmeal porridge (similar to Malawian nsima or Zimbabwean sadza), fried plantains, and steamed yucca:

photos by Andrew Guidone

But Aline wasn’t done. She also made an absolutely outstanding platter of broiled chicken, marinated in parsley, garlic, ginger, white and black pepper, and mustard. And there was a fantastic Yakoma dish called ngunza na gnama, featuring beef and cassava leaves, stewed in a peanut sauce.

So yes, Aline prepared five main dishes and four side dishes — for a group of complete strangers. She even made some amazing homemade hot sauce, featuring scotch bonnet peppers. Epic.

I could go on and on about everything we learned about CAR culture and cuisine from Erick and Aline. Erick regaled us with stories of his travels through the nation, and tales of legendary Central African hospitality. Your car breaks down on the roadside? Don’t worry, help is coming — probably along with an invitation to dinner.

So I suppose that I shouldn’t be surprised that Erick and Aline went so far out of their way for a herd of strangers, but it’s hard not to feel optimistic about the world when you spend a day with these two.

Aline, making us all feel optimistic about the world; photo by Andrew Guidone

This story has an unfortunate epilogue, though. Just a week after our meal, Aline’s only daughter – age 11 – passed away in the Central African Republic. Like many immigrants, Aline was scraping by in a low-paid job as a home health aide, and she sent what she could home to support her daughter. But she hadn’t actually seen her daughter in a few years. I can’t even imagine how awful that is.

Aline, of course, was generous enough to take a day off from work to cook for us, and as a tiny gesture, I’d love to return the favor and help her. After all, she had to buy a plane ticket to CAR on super-short notice, and take a couple of weeks off from work.

And to make things worse, she lost her job soon after returning from the trip — so she’s in rough shape, emotionally and financially.

So we’re hoping to raise $2000 to cover her travel costs for the funeral. I know that it won’t do much to ease the pain of losing her only child, but I just want to be able to say that we’re here for her. If you’d like to contribute, please visit the gofundme page we’ve set up in her honor.

Or… would you prefer to munch an African lunch in exchange for your donation? Maybe, like, an African lunch featuring dishes from four different countries? Then please join us at…

Four Corners of Africa Fundraiser for Aline

Featuring Chef Grace Acheampong

Saturday, March 11

12:00-3:00

Trinity Lutheran Church

164 W. 100th Street, Manhattan

Purchase tickets here…

…or donate here

And if a Saturday African lunch isn’t your cup of tea either, see if you can track down some caterpillars. Trust me, they’re tastier than you think.

|

|

|

Because my life is chewy awesome, I spend countless hours googling certain hard-to-find cuisines. I know: hour after hour with Google probably doesn’t sound like fun. But sometimes I accidentally run into some pretty incredible stuff, like an entire English-language cookbook devoted solely to the food of Oman.

photo by Ariana Lindquist

Felicia Campbell, the author of The Food of Oman: Recipes and Stories from the Gateway to Asia, has had one hell of a fascinating journey to becoming an expert on Omani cuisine. Campbell was raised by a pair of university professors, and she had just started college when 9/11 happened. Her reaction was exactly what you’d expect from a family of academics – or, um, not. She enlisted in the Army, and did a tour of duty as a combat soldier in Iraq.

Like most military personnel, Campbell fell in love with Middle Eastern food, culture, and hospitality, and realized that there was much more to Iraq than she’d been told. “All I knew was the American rhetoric about these people being our enemies,” she told me via phone from Oman. “And then I had the opportunity to go into villages and interact with people, and I was struck by their sense of hospitality. Even though we were uninvited guests in their country, they would invite us in for tea, and we would just start talking.”

More than a decade later, Campbell now lives in Muscat, Oman, and she recently released The Food of Oman, which is the only English-language Omani cookbook currently in print. I literally read the book from cover to cover, as if it were a really tasty novel: Campbell’s book doubles as a cultural memoir, with plenty of insight into Omani culinary life. So even if you’re not much of a recipe-hound, there’s plenty of reason to give it a read.

Here are a few of my favorite highlights from the book and my conversation with Campbell:

When Omani Food Almost Disappeared

When Campbell first proposed writing an article about Omani food for Saveur magazine in 2012, there was a huge problem: at the time, there weren’t actually any restaurants that served traditional Omani food. You could find legions of Levantine, Turkish, Indian, European, and East Asian restaurants in Oman, but Omani cuisine appeared to be dead – at least according to TripAdvisor.

Of course, plenty of Omanis still enjoyed traditional dishes at home, but with some curious twists. Beginning in the 1970s, as oil wealth began to slosh through the economy and women increasingly pursued their own careers, domestic tasks were handled by staff from Indonesia, South Asia, and the Philippines. But as Campbell puts it, this led to an interesting phenomenon of “cook-trading”: the household cooks were taught a few recipes, and whenever a family enjoyed a dish in another family’s home, they would send their cook to learn the recipe from the other household’s cook.

So Omani food hadn’t vanished – it was just hiding beyond the prying eyes of the internet, and had been kept alive primarily by non-Omanis.

photo by Ariana Lindquist

Campbell’s Favorite Omani Recipes

Pretty much every recipe in The Food of Oman sounds amazing. Oman was a major crossroads in spice trading routes, and the cuisine is infused with ingredients from South Asia and East Africa, as well as flavors of the Middle East. Spicy calamari curry, chili-lime chickpeas, and frankincense ice cream? Sign me up.

When I spoke with her, I cruelly asked Campbell to pick a couple of favorites. She said that a Zanzibari version of creamed spinach – simmered in onions, chilies, cumin, and coconut milk powder – was the first Omani dish that she fell in love with.

photo by Ariana Lindquist

Her other favorite sounds even more decadent: musanif djaj, or double-fried chicken dumplings. Basically, you fry something that resembles an Omani version of pancake batter, and then top it with spicy minced chicken, seasoned with ginger, lime juice, garlic, cilantro, and chilies. Then you drizzle it with more batter – and then fry it again. Sounds epic.

looks epic, too (photo by Ariana Lindquist)

And in case you don’t have access to ethnic grocery stores, Campbell’s recipes can be prepared with ingredients from a nice, normal, American grocery store. As she wrote the book, Campbell said that she pictured “a passionate home cook in Middle America.” So even if you’re a long way from the wonders of, say, Kalustyan’s, you’ll be fine.

The Omani Food Renaissance

Interestingly, Omani food is making a resurgence in restaurants now. There are now at least 10 restaurants in Oman that serve the national cuisine, and there are rumors that Oman’s first celebrity chef, Issa Al-Lamki, might open an Omani restaurant overseas. (Please come to New York, Chef!)

Of course, dishes from Europe, the Levant, and Asia remain popular in Omani restaurants, especially in the cities. But international cuisine is primarily a dinnertime phenomenon in Oman. Lunch in Oman has always been centered around Omani rice dishes, which resemble Indian biryanis. “Omanis can eat 20 sandwiches for lunch, but if they haven’t had rice, they swear that they haven’t eaten,” Campbell explained.

So TripAdvisor wasn’t completely bonkers when it claimed that Omani food had been replaced by international cuisine. It’s just that TripAdvisor didn’t know much about lunch.

Zanzibari biryani, featuring double-cooked chicken in rosewater (photo by Ariana Lindquist)

“Everyone loves to eat in Oman, even the glamour girls.”

Perhaps the most interesting bits of the book were Campbell’s insights about Oman’s culture, its extraordinary culinary history, and its enthusiastic embrace of the joy of eating.

Here in America, we tend to have a guilty streak when we eat: it seems like whenever we finish a huge meal, somebody sheepishly mumbles something about needing to go to the gym tomorrow. Maybe that’s not a surprise: after all, we’re the cultural descendants of Puritan colonists, and we’re just a wee bit body-image obsessed.

But Omanis aren’t shy about eating at all, and they enthusiastically embrace food as “a gift from Allah,” as Campbell puts it. In my favorite scene of the book, Campbell dined with a group of fashionable Omani women, and she was worried about the meal: “I was starving, but I wondered if these perfectly coiffed ladies would just nibble daintily.”

Spoiler alert: the meal sounded amazing – and it wasn’t dainty at all.

I don’t know about you, but I think there’s something refreshing and beautiful about a culture that gets so deeply excited about food, without even a hint of shame or sheepishness. Pass the double-fried chicken dumplings, please.

photo by Ariana Lindquist

Do you know anybody who might be willing to prepare Omani cuisine in New York City – or who might just enjoy having a good conversation about Omani food? Email me at [email protected], or connect with me on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram. And check out Campbell’s book – it’s a fascinating read, even if you’re not much of a chef.

|

|

View My Favs!

Search This Blog

Food By Region

|