Sometimes, people are simply amazing.

With mixed success, I’ve been a cold-calling fiend lately: if you’re a UN Mission, a community organization, or a New York-based artist from any of the remaining hard-to-find countries, I’ve probably tried to contact you. I’ve even spent entire rainy afternoons wandering through the Bronx, chasing vague rumors of Gambian cuisine. In my search for Gambian food in New York, I contacted two different Gambian community groups via phone, facebook, and email; nobody responded.

Then I tried a third organization, the Gambian American Network (GAN). A wonderful fellow from GAN named Ansumana was kind enough to put me in touch with a gentleman named Sam, who put me in touch with a wonderful woman named Fatima, who graciously invited me to a Gambian naming ceremony that was taking place just two days later. None of them actually met me in person until I showed up on a Friday afternoon in the Bronx, along with an enormous appetite and my friend Kapambwe, a visiting Zambian student that I was hosting for the weekend.

And it was a good thing that I showed up with an enormous appetite, because our hosts – including Fatima and a dozen other friendly Gambians – generously offered us wave after wave of incredible cuisine.

In case you’re wondering, Gambian naming ceremonies typically take place a week after a child is born. Basically, friends and family gather to decide on a name for the child and celebrate the child’s birth. In spirit, the naming ceremony strikes me as similar to, say, a Greek baptism: sure, there’s a distinct religious and ceremonial component to a Greek baptism, but Greeks get particularly excited the opportunity to throw a huge party and celebrate life.

Incidentally, I hear rumors that Bengalis organize epic celebrations when a child is old enough to eat his or her first solid food. I think that’s absolutely brilliant: “Hey everybody, now that our kid can eat… let’s throw a huge party so we can eat!!”

Anyway, Fatima and her friends and family proceeded to treat us simultaneously like honored guests and long-lost cousins, feeding us plate after plate of outstanding, home-cooked food.

The first plate was one of those dishes that made me squirm with excitement as I ate it. It was groundnut (similar to peanut) stew with lamb – broadly comparable to the Senegalese mafe that’s a staple in New York’s West African restaurants – but this version was homemade, and wonderfully fresh and silky and spicy:

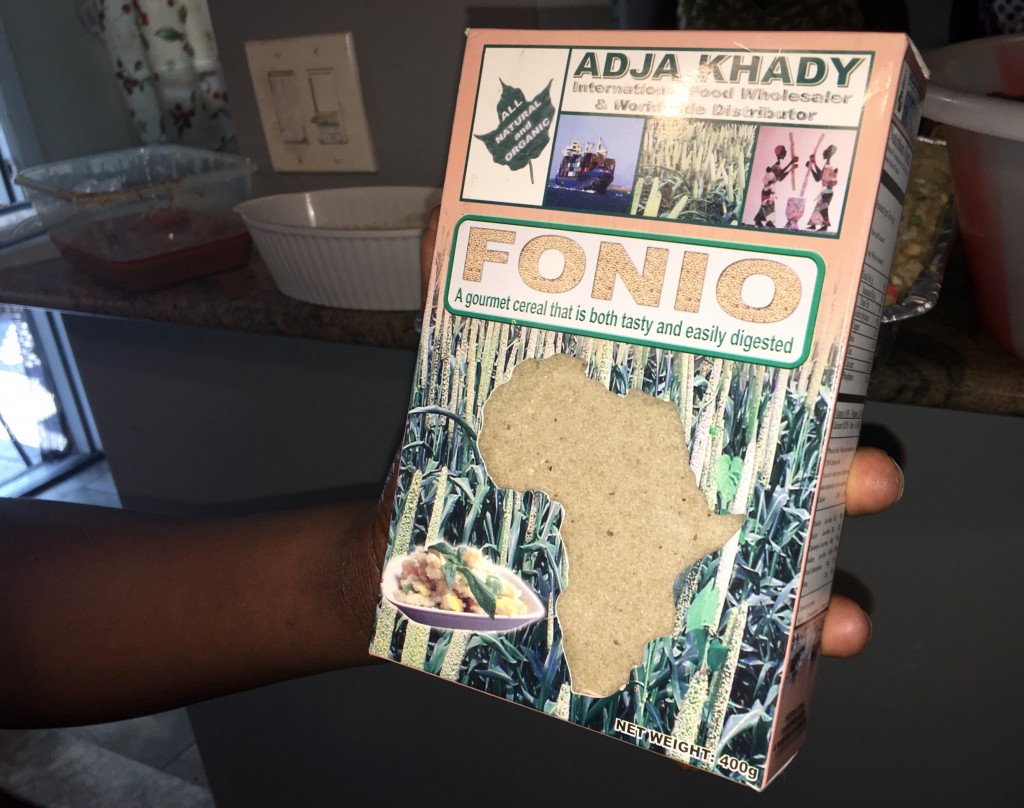

I’ve eaten versions of groundnut stew with all sorts of starches – rice, fufu, couscous, attieke (toasted cassava), and even pasta – but this afternoon’s stew was served with fonio, a millet-like grain from West Africa that I’d never tried before, which had been cooked with blended okra. You couldn’t actually see or taste the okra, but it gave the grain a wonderful consistency.

Interestingly, some West Africans — not including Chef Pierre Thiam — are concerned that wealthy Western consumers will become obsessed with fonio, and make the grain unaffordable in West Africa. Something similar happened with quinoa, which has become less affordable for Bolivians as its popularity exploded in the West. So let’s pretend that I didn’t love it? Moving on.

Anyway, if the groundnut stew had been the end of the meal, Kapambwe and I would have left the Bronx with contented smiles on our faces. We weren’t overstuffed yet, but we certainly weren’t hungry anymore, and we’d just spent a couple of hours with some wonderfully warm and interesting people. But Fatima and the rest of the women were just getting warmed up.

The next round of food featured one of those homemade chunks of chicken that borders on divinity. The chicken had been marinated in a spicy rub spiked with – I think – Maggi and hot peppers, and it was served with a warm, hearty potato salad.

Life felt amazing at that moment. We’d eaten two delicious meals in less than 45 minutes, while chatting with some lovable people. That’s a perfect afternoon, right? We were absolutely stuffed by then, and starting to smile those groggy grins that follow a gargantuan meal.

But we weren’t done. Fatima brought out some large, handmade cornmeal dumplings, reminiscent of fried empanadas, stuffed with bluefish, onions, and spices; she called them domade, but another woman referred to them as fataya. As Fatima put one on each of our plates, I immediately apologized: “I’m already so stuffed – please don’t take offense if I can’t finish it!”

Of course, I finished it, not out of politeness, but because it was absolutely amazing. In related news, I also finished a button on my shirt, which popped off and rolled across the street.

Before we finished the dumplings, Fatima brought out a plate of lamb for each of us, baked in a spicy mustard-onion sauce and finished on a charcoal grill. My buddy Kapambwe – who, incidentally, had only eaten a little bit of bread all day – begged for mercy. I told Fatima that we’d share a single plate; Kaps insisted that he couldn’t eat another bite. But the lamb was so darned good that we finished the plate.

By then, the two of us had eaten a total of five plates of food and two large fried, fish-stuffed dumplings. In related news: I might have broken a chair. We were already running late for our next meal, so we started preparing to leave. Fatima insisted that we couldn’t leave without trying one last treat: thiakry, a pudding-like mix of sweetened yogurt and sour cream, topped with millet and raisins.

I insisted that I really couldn’t eat another bite, but didn’t want to be rude, so I tried it. Kaps did the same, then ended up taking the rest home.

I ate all of mine. Thiakry is vaguely similar in spirit to the yogurt-granola parfaits that have become fashionable, except that it’s actually amazing: Fatima’s version tasted incredibly fresh and not terribly sweet, with a nice, chewy texture provided by the millet. After we were finished eating, Fatima generously offered us a ride to the subway station, so that we could make it to our next meal on time.

Incidentally, this meal took place on Kapambwe’s very first day in New York City, and his friends in Rochester had warned him that he should avoid the Bronx because it’s dangerous. I hate that stereotype — why do people think that the Bronx is filled with monsters? Kapambwe – who is far too smart to believe lame stereotypes about the Bronx or anywhere else – thought that was pretty funny, and we took as many selfies as we could with signs containing the word “Bronx” or “Bronxwood.”

So yeah: instead of running into danger, he met some of the most genuinely kind and open people you’ll ever meet in New York – or anywhere else. Things work out.

Huge thanks to Fatima, Asumana and Sam at the Gambian American Network, and all of the wonderful people I met at the naming ceremony. If you have comments or suggestions — or can help me track down other hard-to-find African cuisines — please email me at [email protected], or connect with me on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram.