|

|

Pretty much my entire life revolves around hard-to-find international foods, but this is one of my favorite finds ever: I just ate in the world’s only Mauritanian restaurant outside of Mauritania.

Here’s the story: I contacted absolutely everybody I could find from Mauritania. Unfortunately, that was only one guy: a fellow named Nasser Wedaddy, who is listed in Wikipedia as the only prominent Mauritanian-American who actually lives in the United States. His home is in Boston, but he agreed to speak with me after I tweeted at him a couple of times.

Nasser is pretty much a walking encyclopedia of Mauritanian history, politics, and culture, and I can’t possibly do our conversation justice here – after all, you probably just visited this food blog for pictures of couscous, right? But I was riveted by everything Nasser had to say about Mauritania. He described Mauritania as “the most African Arab country,” thanks to the country’s mix of Bedouin and other African cultures. West African standards like mafe and yassa and thiebu djen are popular in Mauritania, though they’ve been “Mauritanian-ized” to suit local tastes and ingredients.

And of course, Mauritania has plenty of fascinating native treats that probably merit their own book: sea turtle soup; a haagis-like dish called kouzo-nouzo, made with barbecued offal; a variety of beverages made from baobab (“monkey fruit”) that are known to cure diarrhea; bread that’s baked underground, in a particular type of hot sand; a regional delicacy made from camel hump and liver; and countless variations on couscous, which are made from a wide variety of grains, including fonio, cassava, and millet. Apparently, you can even get a camel milk latte in Mauritania if you know where to look.

It was distressing to hear Nasser discuss the changes in Mauritania over the past 40 or 50 years. The country – and its traditional foodways – have been throttled by climate change since the 1960s or 1970s, as a massive, long-term drought turned huge swaths of the country into desert. Sadly, only a tiny percentage of the country’s traditional nomads maintain any semblance of their traditional lifestyle. And Nasser always has plenty of fascinating things to say about Mauritanian and international politics – check out his always-interesting Twitter feed for more.

And my ears perked up when I heard a few magic words from him: there’s a Mauritanian restaurant in Montreal.

I’d just been invited to a magnificent East Timorese dinner in Canton, New York – two hours from Montreal. So, um… well, what a coincidence! I guess I’m going to Montreal.

La Khaïma, in Montreal’s legendary Mile End neighborhood, isn’t really a restaurant. I mean, sure: they bring you food, and you pay them money. But it’s more like a work of cultural art, channeling the spirit of Mauritanian nomads in the heart of Montreal. When you walk in, you remove your shoes, and take a seat on a cushion on the floor. The walls and ceilings are covered in tapestries that owner Atigh Ould brought back from his homeland. And there are no printed menus: it’s as if you’re eating in the home of a Bedouin nomad, and you’re offered whatever fresh food happens to be available that day.

On this particular day, we started with a bright, citrusy hummus, served with pita bread:

Round 2 consisted of an outstanding bowl of harira soup, featuring lentils, chickpeas, vermicelli, vegetables, and plenty of cumin:

For our main course, we shared a communal bowl with three different types of couscous: beef with okra; a vegetarian stew featuring carrots, squash, and potatoes; and chicken cooked with green olives:

There was something particularly magical about the chicken-olive couscous. Here, take a closer look:

mmm, olives

For dessert, we enjoyed a treat that resembled a honey-soaked banana bread, served with a delicious, lightly sweetened mint tea:

All four courses were fantastic, but that’s not necessarily the point. La Khaïma is one of those unhurried, relaxed places where you instantly feel like a member of the family. We lingered for about two and a half hours; two neighboring tables of relaxed Francophones lasted even longer. It’s like we all just decided we lived there.

And our wonderful, warm, relaxed server pretty much acted like we were members of the family. We told him how much we loved the chicken and olive couscous in particular; when he packed our leftovers in a to-go box, he very generously added a pile of extra chicken.

And that was before he knew that the chicken would be making an international journey for a glamorous photo shoot in New York City’s Grand Central Station.

and what’s more glamorous than a nomadic Tupperware in a train station?

As great as the dinner was, it wasn’t even the best part of our visit.

As we were leaving, the owner, Atigh, arrived after a night of Mauritanian music at the Montreal Jazz Festival. His reappearance was fortuitous, because I was under strict instructions from Nasser Wedaddy, the wonderful Boston-dwelling Mauritanian who had sent me to La Khaïma: call me when you arrive, and pass the phone to Atigh.

And damn, I wish I had taken a picture when I handed him the phone. Atigh and Nasser grew up together in Mauritania, and the Wedaddy family is legendary in their homeland: Nasser’s father had brought radio broadcasting equipment via camel from Senegal, and introduced a nightly broadcast for the nation’s nomads. He’s credited as one of the men who helped unify modern Mauritania, and he later served as a diplomat, among other things.

And when he heard Nasser’s voice on a random visitor’s cell phone, the look on Atigh’s face was absolutely priceless.

Atigh, after recovering from Wedaddy-induced shock

Even more priceless: a long evening with Atigh, drinking tea and learning about Mauritania and Montreal. I can’t even begin to describe everything we learned about Mauritania that night. Nasser and Atigh need to co-author a book, and you probably need to read it.

Atigh fascinated us with descriptions of the traditional nomadic lifestyle: Atigh’s forebears would move from location to location based on cues from the shifting winds, which would tell them when to migrate to the date groves or to the coast for a seasonal bounty of fish. Even more amazing: apparently, patches of the Atlantic ocean actually contain fresh water, desalinated by a particular aquatic plant that the nomads had learned to identify.

In his restaurant, Atigh seems determined to embody the spirit of Mauritanian nomad hospitality in everything he does. The meals are seasonal, and based on local ingredients wherever possible. He has developed relationships with local producers, including a bunch of students who produce some remarkably tasty blue kale on a decidedly non-commercial scale. And many of the spices used in the cuisine are grown on Atigh’s own land in Mauritania, which he visits once or twice a year.

Atigh also insists that he’s a terrible salsa dancer; so bad, in fact, that the salsa school he attended for nearly a year refunded his tuition. I am not making this up.

Despite his lack of salsa skills, the man is a ton of fun. He loves to mess with stressed-out customers, telling them rambling stories about how there isn’t any food today because his brother back in Africa can’t find his camels, just to see the look on their faces. Of course, there’s always food at La Khaïma – but sometimes, eat-and-run Westerners deserve to be messed with.

And there’s always tea at La Khaïma. Atigh generously prepared a special pot of tea for us — at nearly midnight, after the restaurant had closed — made from a mix of mint and jasmine tea leaves. He energetically poured the tea from a dizzying height, then quickly poured it from glass to glass, then back into the pot. He did this repeatedly, until the tops of our glasses were frothy:

getting frothier…

As it turns out, aerating the tea improves the flavor, and the oxygenated tea is also thought to cure headaches. This was among the most delicious teas I’d ever tasted; I’m not sure whether it was the high-altitude pour, or just Atigh’s artful blend of fresh tea leaves.

Once we finished our tea, Atigh took us on a tour of his beloved Mile End neighborhood, home to Wilensky’s legendary sandwich shop, where mustard is not optional. Atigh also took us to visit his friends at Fairmount Bagels, an infamous 24-hour bakery that makes bagels in a wood-fired oven – with honey, sesame seeds, and egg – literally all night long.

So yeah: I was eating Montreal bagels – straight from a wood-fired oven – at 1:30 in the morning with the western world’s only Mauritanian restaurateur, in front of an eccentric 80-something-year-old sandwich shop. I was in heaven.

legends of Mile End

There was only one problem: Montreal is not New York City, and… well, you know, I have rules or something. So I smuggled some leftover couscous with chicken and olives across the border, took a few photos of the meal in Grand Central, and then ate it in front of a Tim Horton’s in Midtown. Somehow, that felt appropriately Canadian – and appropriately nomadic.

La Khaïma

142 Avenue Fairmount Ouest

Montreal, Canada

I know: I get an asterisk for this. Know anybody in NYC who might be willing to prepare Mauritanian dishes or other hard-to-find cuisines? Please email me at [email protected], or connect with me on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram.

|

|

|

I seem to say the same thing after every single meal these days: people are amazing.

In my search for Timorese food, I emailed some complete strangers in East Timor – alumni of my high school’s “sister school” – and asked if they knew any Timorese people who live in New York. Within a few hours, the friendly Timorese strangers had contacted a thoroughly lovable St. Lawrence University student named Debby, who emailed me immediately. As luck would have it, two of Debby’s Timorese friends were visiting her for a night of Timorese cuisine – and Debby very generously invited me to join the fun.

In case you’re not familiar with it, St. Lawrence University is in the charming little town of Canton, New York – about 350 miles from New York City. I know: I deserve an asterisk for leaving the five boroughs. But the capital of East Timor is 9,900 miles from here. A 350-mile drive is a drop in the bucket, right?

Plus, I absolutely loved my hosts, and would drive 350 miles anytime just to hang out with any of them again. The threesome consisted of Jacky, a student of food processing in upstate New York; Miguel, a rising senior (and soccer star!) at Methodist University in North Carolina; and Debby, our beloved ringleader, working on a degree in economics and politics at Saint Lawrence.

East Timorese dream team of upstate New York

East Timor is pretty literally on the opposite end of the planet, but the world is small sometimes: Jacky and Debby attended the same high school in Dili, then ended up in the same region of New York as university students. Miguel and Debby met at an international school in Singapore – where they discovered that they were actually related, even though they’d never met before.

Anyway, we spent a solid five hours in the shared kitchen of St. Lawrence’s International House, eating an amazing meal and chatting about East Timor. My three hosts are fantastic conversationalists who taught me TONS about their country in just one evening. And of course, they fed me a wonderful, wonderful meal.

Let’s start with the ludicrously delicious fish – tilapia, I think – brushed with garlic and chile oil, and grilled on one of those slick little plug-in grills. It’s amazing what you can do in a dormitory kitchen these days, no?

The other main course was my very favorite dish of the night: a work of slow-cooked genius called koto. There’s a lot going on here: stewed sausage, pork, kidney beans, carrots, potatoes and pasta, seasoned with ginger and molho – a sauce made from garlic, onion, and tomato, stir-fried in chile oil. It was one of those fantastically flavorful stews that you can’t help but love.

And yeah, I know: this is “just” rice, but it was cooked in coconut water, and then finished in a steamer placed atop the water used to cook some of the koto ingredients. If it was possible to make the koto even tastier, coconut-infused rice will do the trick:

Incidentally, it sounds like amazing things routinely happen to rice in East Timor. Miguel told me about a dish made from lightly fermented rice, wrapped in a banana leaf and char-grilled. It sounds amazing.

Desert was pretty amazing, too. We ate something called pudim, and I’m not sure whether you’d describe it as an incredibly moist, pudding-like cake, or a wonderfully cake-y pudding. Either way, it was delicious – vaguely reminiscent of a top-notch flan, but less jiggly:

As is often the case these days, the food was great, but the conversation with Jacky, Miguel, and Debby was even more amazing. If you’re an American of a certain age, you might remember hearing about the country’s long struggle for independence from Indonesia, which lasted from the early 1970s – when Portugal, the previous colonial ruler, stepped aside – until East Timor formally won its independence in 2002.

But I can’t remember seeing any mention of East Timor in the American media since then, unfortunately.

And that’s a shame, because the place sounds fascinating: it’s a country with incredible natural biodiversity – and food and cultural diversity – despite being roughly 1/10 the size of North Carolina. More than 30 different languages are spoken in the country, and this is the source of some fascinating twists in Timorese life: when Debby and Jacky were in high school, the national exams suddenly shifted from Indonesian (spoken by most of the teachers) to Portuguese (the new language of national unity, spoken as a mother tongue by virtually nobody in the country). I’m sure that the students were not terribly thrilled to take those tests, particularly considering that relatively few Timorese speak either of those two languages at home.

This is unimaginable to Americans. Sure, some people in the United States struggle to learn English, but there’s no question about what the lingua franca is. In East Timor? It depends on what part of the country you’re in and who you’re talking to.

Even more fascinating: Miguel and his father have been documenting several of East Timor’s regional languages, in an effort to preserve them. Again, this is unimaginable to most Americans, though New York is – quietly – a reservoir of endangered world languages.

But you probably came here for food pictures. So here, have one more:

Before I left Canton, I asked Debby if she had any favorite spots in New York City; she replied that she particularly loves the Brooklyn Bridge. So I brought the leftover koto for a glamorous photo shoot on the Brooklyn Bridge.

And the koto looked even more dazzling next to the New York City skyline on the south side of the bridge:

So now you know a small international secret: East Timorese food – in any language – is so good that it doubles as a supermodel.

Huge thanks to Debby, Jacky, and Miguel for the amazing meal and conversation. Got questions, complaints, or feedback — or do you just feel like having a conversation about other hard-to-find cuisines? Email me at [email protected], or connect with me on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram.

|

|

|

I was drinking beer at an alumni happy hour a few weeks ago, and I kept thinking to myself: “You know, I’ve never even met anybody from Zambia or Zimbabwe. Ever. I mean, I’ll probably find those cuisines in New York City only when pigs fly through the 86th Street subway station…”

woah

As luck would have it, I was chatting with a friendly Canadian named Jaime at that happy hour, and after I finished describing my project, I half-jokingly said, “Yeah, so, um, if you happen to know anybody from Zimbabwe who might want to cook for me, let me know!”

Her response? “My roommate is from Zimbabwe. She’d totally cook!”

At around the same time, I received an email from a Zambian student at the University of Rochester, who will probably be the president of Zambia someday. When he was still in high school, this guy recognized that flies – and the diseases they carry – were harming small-scale chicken farmers in Zambia, and he designed a dirt-cheap flytrap made from recycled soda bottles. He also launched a campaign through the Zambian human rights council to eliminate hazing and beatings at his high school.

This guy is brilliant and ballsy. Start printing the 2030 campaign posters now: Kapambwe Chalwe for President of Zambia.

small kitchen filled with mealie, ginger beer, and international brainpower

Anyway, he just finished the first year of his biomedical engineering program in Rochester, and when he contacted me, he hadn’t seen anybody from his country since arriving in the United States a year ago. He had somehow heard about my project, and emailed me to ask if I could help him find some kindred spirits from Zambia – or from neighboring countries.

I answered that I didn’t know any Zambians, but I’d be happy to take him to the Zambian UN Mission – and I’d be thrilled to introduce him to a Zimbabwean I hadn’t met yet.

Next thing I knew, we were all crammed into a kitchen, making Zambian and Zimbabwean food. Actually, it was better than that: a wonderful friend of mine named Irene very kindly allowed us to trash borrow her apartment to host an international potluck. Attendees included folks from Senegal, Uganda, Saudi Arabia, Central African Republic, and Nicaragua, as well as an African Studies professor who makes an excellent South African bobotie — a wonderfully spiced South African casserole that vaguely resembles a good Greek moussaka.

bobotie in the lower-left corner; if you can name the other dishes, you deserve a rosquilla

But the stars of the evening were our wonderful Southern African chefs-for-a-night. Tendai, our Zimbabwean chef, is every bit as accomplished as Future President Kapambwe: she’s currently working on a PhD in Public Health at Columbia, and just oozes with low-key genius when you meet her. Jaime, the Canadian graduate student who graciously spent hours helping out in the kitchen, is currently working on a public health project in Tanzania.

So there was some serious brainpower in that little kitchen.

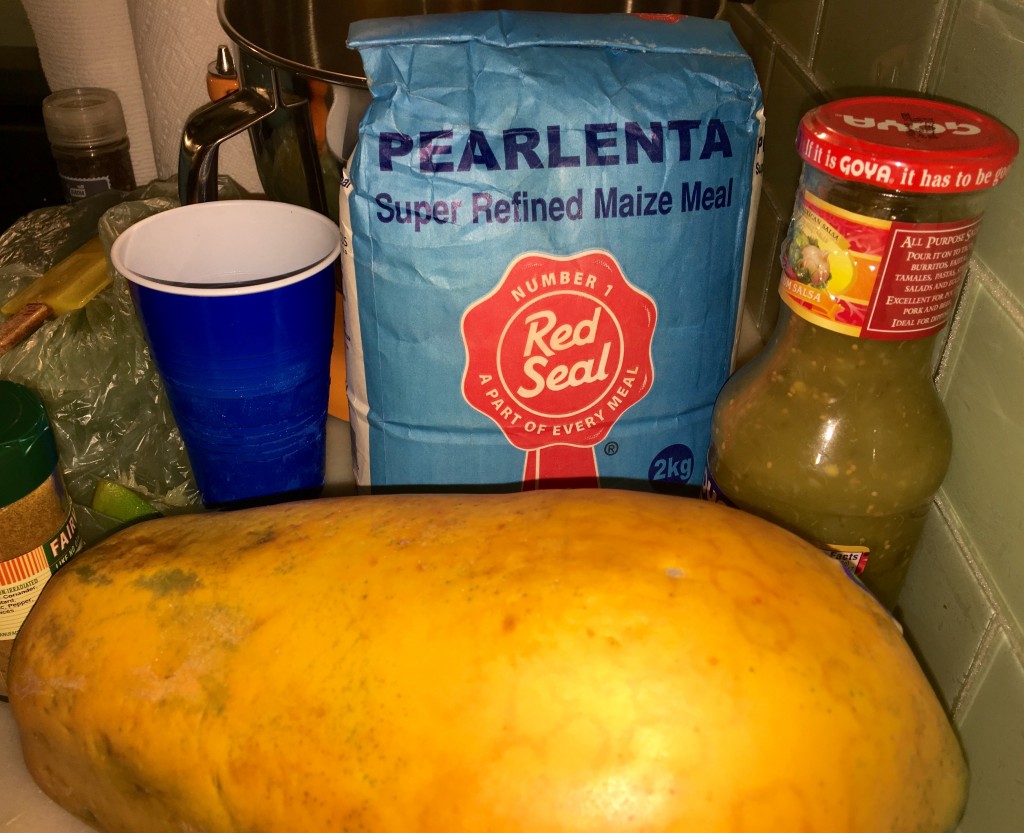

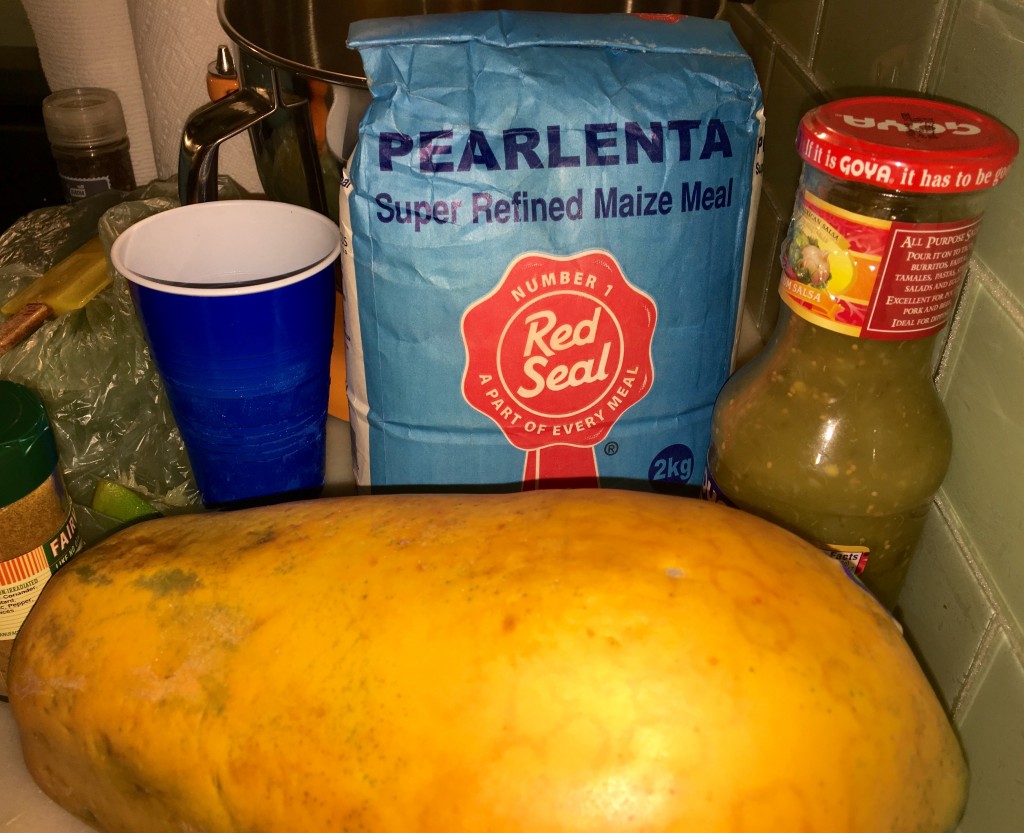

There isn’t necessarily a clear difference between Zambian and Zimbabwean cuisine: both countries enjoy white cornmeal as the main staple, called nshima in Zambia and sadza in Zimbabwe (and nsima in Malawi and sishwala in Swaziland and mealie in Namibia…). Pieces of sadza are then used as a utensil to scoop any variety of stews, generally made from some combination of meat and/or vegetables.

mealie!

On this particular night, Tendai brought the cornmeal for the sadza, procured from a Zimbabwean woman who sells it to her countrymates in New York. There’s an art to making great sadza, which should be smooth, but firm enough to maintain its shape on your plate. Too much or too little water can ruin a batch of sadza, and you need a large, flat wooden spoon to pound out the lumps and ensure a smooth consistency.

And that’s where things got difficult: the only wooden spoon we had was small and round, so poor Kapambwe put in a Herculean effort. He was sweating like crazy as he tried to smooth out one half of the pot at a time, working frantically with the runty spoon.

The guy deserved the excellent meal that followed. Hell, he also deserved an amazing Gambian meal, but that’s another story.

To go along with the sadza, Kapambwe made an excellent stew of collard greens with onions. Apparently, the secret to a great plate of Zambian-style greens is cutting the greens with incredible precision. Seriously, I think he might have spent an hour just shaving the greens to perfection.

But my very favorite dish was the Zimbabwean-style stewed beef that Tendai made. It was an incredibly simple dish: t-bone steak, carrots, onions, garlic, and salt, simmered for hours until the meat fell off the bone. That’s it.

You know how a perfectly cooked steak or an expertly roasted chicken can border on divinity, even if they’re seasoned with nothing but salt? This beef dish was the same way: it was outstanding, and disappeared from the buffet table within a few minutes.

Of course, this was an evening of broader excessive decadence. There was a great South African malva pudding, made by our (American) hostess. And some Indian golab gamun brought by a Saudi, dumplings and couscous brought by our Ugandan and Senegalese pals, and some rather strong drinks made by some American whacko. There were even Nicaraguan rosquillas – savory cookies that my friend Eduardo brought back from a visit to his mom’s house in Nicaragua:

So yeah: I think we crammed food from 10 nations on that table. Life is pretty fantastic.

Thank you to everybody who helped bring this incredible group of people together: Jeff, Nick, Meg, Erick, Andres, Eduardo, Moussa, Brian from We Dream Africa, Brian Feldman, Zainab, and especially Tendai (our Zimbabwean chef for the night), Jaime (for bringing Tendai!), Kaps (our Zambian chef for the day), and Irene, who graciously allowed us to wreck her kitchen for the night. I still owe you a new ceiling fan bowl, Irene!

If you have comments or suggestions — or want to prepare other hard-to-find cuisines for the next potluck — please email me at [email protected], or connect with me on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram.

|

|

|

Sometimes, people are simply amazing.

trust me: these ladies are amazing

With mixed success, I’ve been a cold-calling fiend lately: if you’re a UN Mission, a community organization, or a New York-based artist from any of the remaining hard-to-find countries, I’ve probably tried to contact you. I’ve even spent entire rainy afternoons wandering through the Bronx, chasing vague rumors of Gambian cuisine. In my search for Gambian food in New York, I contacted two different Gambian community groups via phone, facebook, and email; nobody responded.

Then I tried a third organization, the Gambian American Network (GAN). A wonderful fellow from GAN named Ansumana was kind enough to put me in touch with a gentleman named Sam, who put me in touch with a wonderful woman named Fatima, who graciously invited me to a Gambian naming ceremony that was taking place just two days later. None of them actually met me in person until I showed up on a Friday afternoon in the Bronx, along with an enormous appetite and my friend Kapambwe, a visiting Zambian student that I was hosting for the weekend.

And it was a good thing that I showed up with an enormous appetite, because our hosts – including Fatima and a dozen other friendly Gambians – generously offered us wave after wave of incredible cuisine.

hand-making the dumplings, called fataya or domade

In case you’re wondering, Gambian naming ceremonies typically take place a week after a child is born. Basically, friends and family gather to decide on a name for the child and celebrate the child’s birth. In spirit, the naming ceremony strikes me as similar to, say, a Greek baptism: sure, there’s a distinct religious and ceremonial component to a Greek baptism, but Greeks get particularly excited the opportunity to throw a huge party and celebrate life.

Incidentally, I hear rumors that Bengalis organize epic celebrations when a child is old enough to eat his or her first solid food. I think that’s absolutely brilliant: “Hey everybody, now that our kid can eat… let’s throw a huge party so we can eat!!”

Anyway, Fatima and her friends and family proceeded to treat us simultaneously like honored guests and long-lost cousins, feeding us plate after plate of outstanding, home-cooked food.

The first plate was one of those dishes that made me squirm with excitement as I ate it. It was groundnut (similar to peanut) stew with lamb – broadly comparable to the Senegalese mafe that’s a staple in New York’s West African restaurants – but this version was homemade, and wonderfully fresh and silky and spicy:

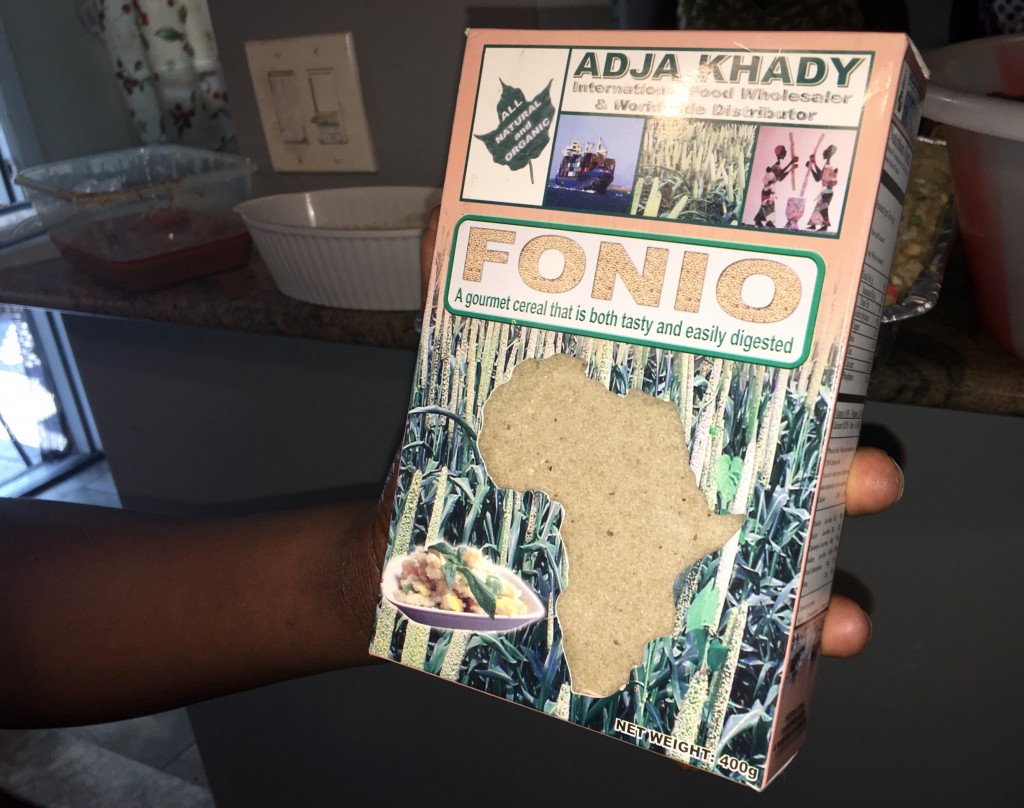

groundnut stew: a love story

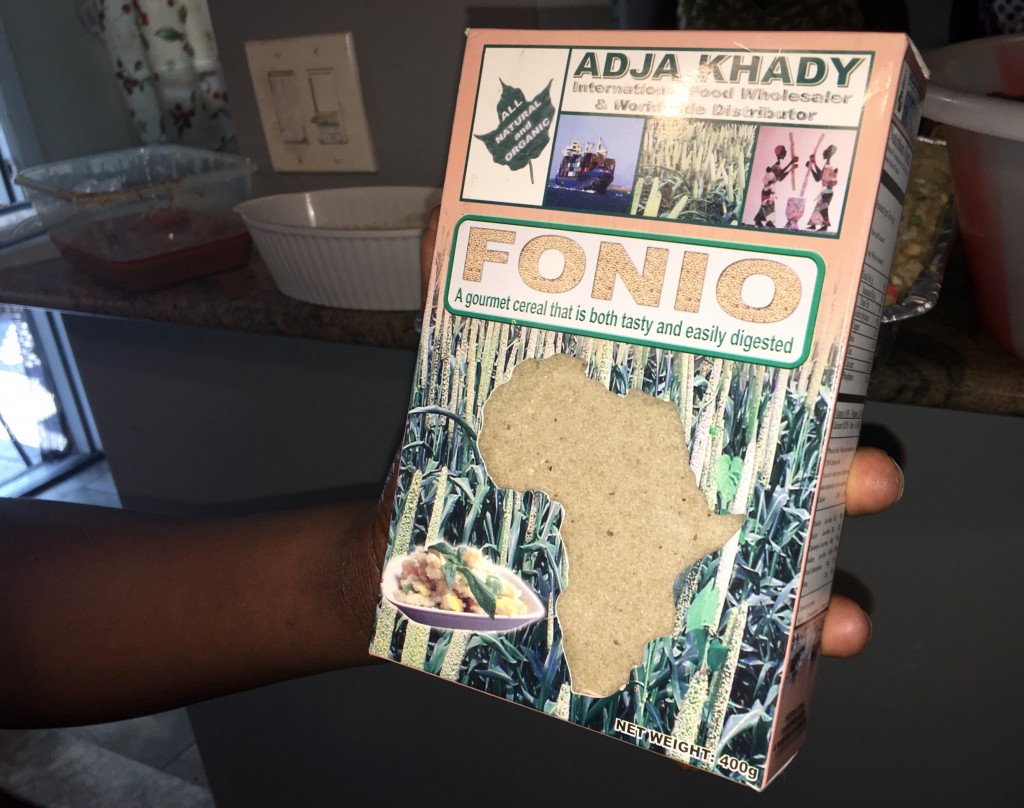

I’ve eaten versions of groundnut stew with all sorts of starches – rice, fufu, couscous, attieke (toasted cassava), and even pasta – but this afternoon’s stew was served with fonio, a millet-like grain from West Africa that I’d never tried before, which had been cooked with blended okra. You couldn’t actually see or taste the okra, but it gave the grain a wonderful consistency.

fonio… shhhhhhhhh!

Interestingly, some West Africans — not including Chef Pierre Thiam — are concerned that wealthy Western consumers will become obsessed with fonio, and make the grain unaffordable in West Africa. Something similar happened with quinoa, which has become less affordable for Bolivians as its popularity exploded in the West. So let’s pretend that I didn’t love it? Moving on.

Anyway, if the groundnut stew had been the end of the meal, Kapambwe and I would have left the Bronx with contented smiles on our faces. We weren’t overstuffed yet, but we certainly weren’t hungry anymore, and we’d just spent a couple of hours with some wonderfully warm and interesting people. But Fatima and the rest of the women were just getting warmed up.

The next round of food featured one of those homemade chunks of chicken that borders on divinity. The chicken had been marinated in a spicy rub spiked with – I think – Maggi and hot peppers, and it was served with a warm, hearty potato salad.

Life felt amazing at that moment. We’d eaten two delicious meals in less than 45 minutes, while chatting with some lovable people. That’s a perfect afternoon, right? We were absolutely stuffed by then, and starting to smile those groggy grins that follow a gargantuan meal.

But we weren’t done. Fatima brought out some large, handmade cornmeal dumplings, reminiscent of fried empanadas, stuffed with bluefish, onions, and spices; she called them domade, but another woman referred to them as fataya. As Fatima put one on each of our plates, I immediately apologized: “I’m already so stuffed – please don’t take offense if I can’t finish it!”

Of course, I finished it, not out of politeness, but because it was absolutely amazing. In related news, I also finished a button on my shirt, which popped off and rolled across the street.

fataya or domade; busted shirt not pictured

Before we finished the dumplings, Fatima brought out a plate of lamb for each of us, baked in a spicy mustard-onion sauce and finished on a charcoal grill. My buddy Kapambwe – who, incidentally, had only eaten a little bit of bread all day – begged for mercy. I told Fatima that we’d share a single plate; Kaps insisted that he couldn’t eat another bite. But the lamb was so darned good that we finished the plate.

delicious grilled lamb; busted chair not pictured

By then, the two of us had eaten a total of five plates of food and two large fried, fish-stuffed dumplings. In related news: I might have broken a chair. We were already running late for our next meal, so we started preparing to leave. Fatima insisted that we couldn’t leave without trying one last treat: thiakry, a pudding-like mix of sweetened yogurt and sour cream, topped with millet and raisins.

I’m bad at math, but I think this is our fifth serving of food

I insisted that I really couldn’t eat another bite, but didn’t want to be rude, so I tried it. Kaps did the same, then ended up taking the rest home.

I ate all of mine. Thiakry is vaguely similar in spirit to the yogurt-granola parfaits that have become fashionable, except that it’s actually amazing: Fatima’s version tasted incredibly fresh and not terribly sweet, with a nice, chewy texture provided by the millet. After we were finished eating, Fatima generously offered us a ride to the subway station, so that we could make it to our next meal on time.

Incidentally, this meal took place on Kapambwe’s very first day in New York City, and his friends in Rochester had warned him that he should avoid the Bronx because it’s dangerous. I hate that stereotype — why do people think that the Bronx is filled with monsters? Kapambwe – who is far too smart to believe lame stereotypes about the Bronx or anywhere else – thought that was pretty funny, and we took as many selfies as we could with signs containing the word “Bronx” or “Bronxwood.”

So yeah: instead of running into danger, he met some of the most genuinely kind and open people you’ll ever meet in New York – or anywhere else. Things work out.

He looks very, very scared during his post-meal food coma, right?

Huge thanks to Fatima, Asumana and Sam at the Gambian American Network, and all of the wonderful people I met at the naming ceremony. If you have comments or suggestions — or can help me track down other hard-to-find African cuisines — please email me at [email protected], or connect with me on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram.

|

|

|

One of the small perks of being a food blogger is that you occasionally get invited to random, interesting meals. Yes, of course they’re designed as marketing opportunities. But sometimes, they’re pretty darned fun, anyway.

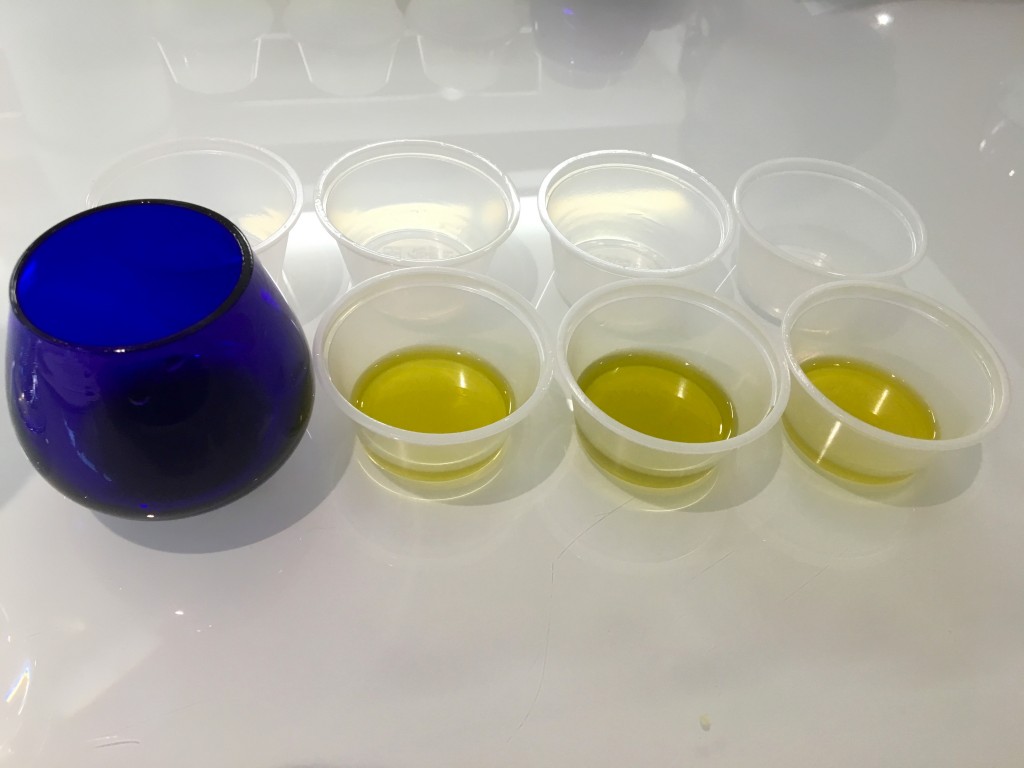

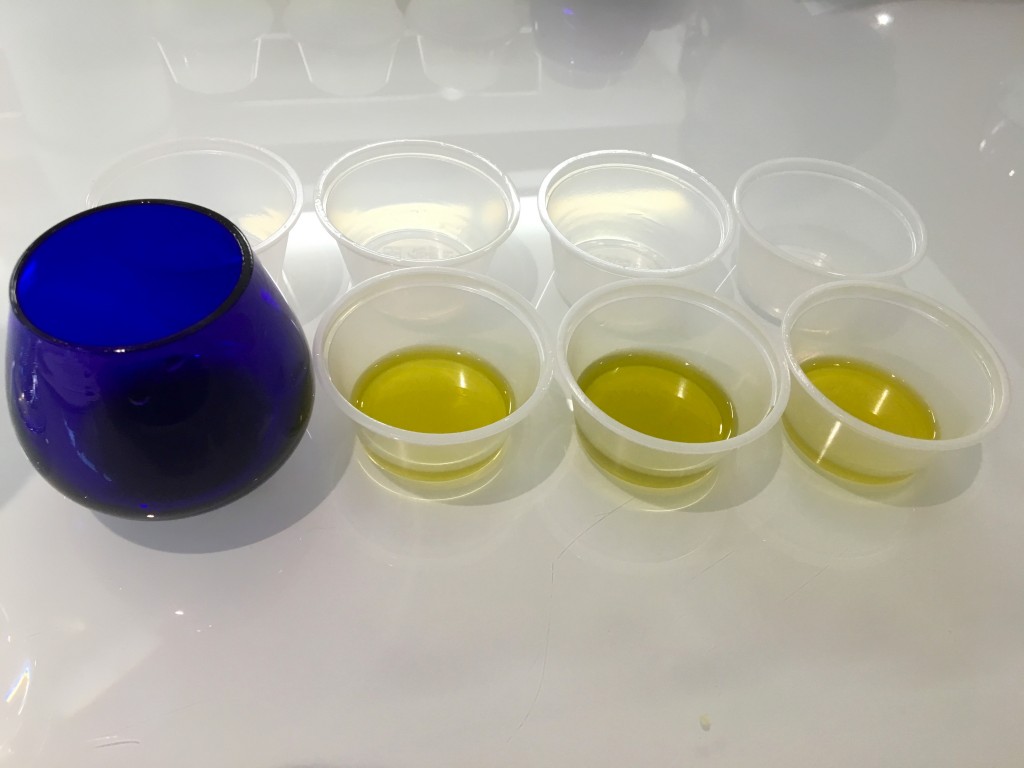

So I was invited to an olive oil tasting – and I probably wouldn’t have guessed that such a thing existed. The event, called Flavor Your Life, was sponsored by the Italian government and the European Union, and featured products made by Farchioni, a large, family-owned Italian producer of all sorts of tasty treats, like beer, wine, pasta, and… well, olive oil. Our hosts for the evening included an all-star team of Italians, including Chef Andrea Tiberi (who traveled from Umbria for the event!), Lou DiPalo of Di Palo’s Fine Foods fame, and a charming fellow named Marco Farchioni, whose family has owned the eponymous company for about as long as the United States has existed.

shots for everybody!!!

Olive-oil tasting, as it turns out, is very much an acquired skill. If you’re really good at it, you could even get a job as an inspector for the Italian government: to be classified as extra-virgin olive oil, the stuff has to be tasted by a highly trained expert. I am not making this up.

For whatever it’s worth, I would be a pretty lousy olive oil inspector. We sampled four different oils from different regions of the world, all produced by Farchioni. Some of the oils’ superficial differences were obvious enough: some taste a little bit grassier than others, and some have slightly different hues, though we learned that the color of olive oil has nothing to do with its quality or flavor.

Here’s the really interesting part: different olive oils can seem more or less… spicy, sort of. You’ll literally feel a different peppery pinch in the back of your throat, depending on the quality and origins of the oil. Hm.

Unfortunately, some of the nuance was lost on my rookie palate, and nobody will hire me as an olive oil inspector anytime soon. But if there’s a gig as a pasta, roasted goat, or cornmeal inspector, sign me up.

Anyway, our hosts kindly treated us to a four-course meal featuring plenty of olive oil. We started with an excellent farro, lentil, tomato, and asparagus salad:

seasoned with high-quality olive oil, of course

And then there was a trio of bruscetta:

adorned with — wait for it — olive oil!

For our main course, we enjoyed a nice plate of pasta with cheese and truffles:

with maybe possibly a few dashes of olive oil

And for dessert, a nice panna cotta, with just the right amount of sweetness and jiggle:

And here’s the other random thing I learned while we ate that tasty truffle-y pasta: in Italy, truffles aren’t hunted by pigs because Porky is apparently too hard to control when he gets excited. Italians use dogs instead, who will happily surrender the truffle in exchange for a dog treat.

So yeah: olive oil can taste peppery, and pigs are not ideal truffle hunters. Who knew?

selfie taken during my last truffle hunt

|

|

View My Favs!

Search This Blog

Food By Region

|